Rett syndrome is a rare disorder with a classic presentation, as well as several variants with differing symptoms. It is generally caused by a random mutation in the MECP2 gene and causes a developmental regression in children, in which they begin to lose fine motor skills and other acquired skills within the first 7-18 months of life. Those affected by Rett syndrome develop normally up until the onset of symptoms. Symptoms can be severe but generally progress and the children could begin to develop autistic behaviors as well as seizures. Rett syndrome rarely affects males, as it is an X-linked gene. Symptoms have a range and can be very mild, or severe. Symptoms include loss of control over voluntary movements (walking, crawling), compulsive hand movements (clapping, washing), difficulty swallowing, and microcephaly (Neul & Eskind, 2023).

Rett syndrome occurs in various stages with standard progression. After initial onset of symptoms, affected children go through a stage of rapid deterioration from the age of about 1 to 4 in which their symptoms progress over short periods of weeks or months. The next stage is characterized by a plateau of symptoms, sometimes with a slight improvement in speech and motor skills. In later stages, children with Rett syndrome slowly lose their mobility but can maintain most of their cognitive ability.

The exact cause of Rett syndrome is unknown, but it is generally caused by random mutations in the MECP2 gene, which may lead to protein production problems in the developing brains of those with the mutations. Males with Rett syndrome typically die before infancy, due to the male chromosomal arrangement of XY. There are no known risk factors, but there may be a higher risk in families with a history of Rett syndrome, although this is not confirmed by any study (Mayo Clinic, 2022).

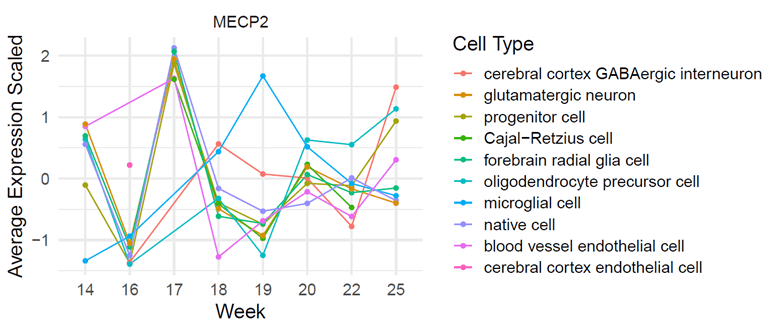

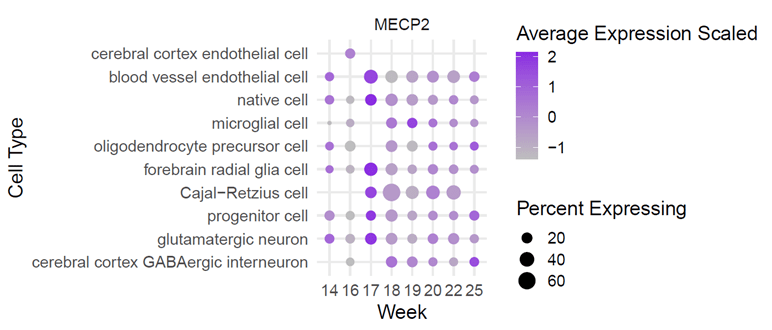

Using the tool, NeuroTri2-VISDOT, to study the MECP2 gene, it is readily apparent that the MECP2 gene is highly expressive in the Cajal-Retzius (CR) cells at 18 weeks (Fig. 1; Fig. 2; Fig. 3). CR cells are responsible for organization of neurons in the fetal brain. This allows neurons to be sent to various layers of brain tissue. CR cells are also known to attract early serotonin input, which may allow for synaptic contact in neurons. Reelin is a protein secreted by CR cells which allows CR cells to control the detachment of radial glia and the organization of the layers of the cortex.

CR cells in Alzheimer’s patients are diminished in number and have decreased synaptic contact with adjacent cells, making them less useful. In patients with schizophrenia, the protein reelin is decreased by half. There are also structural problems in the neocortex of those with autism. It is theorized that these two errors occur at some point between the first and second trimester and involve CR cells. These cells are vital to the proper growth and development of the fetal brain, making it an important aspect to study while hypothesizing the relationship between CR cells, the MECP2 gene, and Rett syndrome.

Patients with the Rett syndrome phenotype have several morphological mutations in the layers of their brain. There is a marked reduction in the volume of gray and white matter, as well as the reduction in volume of the entire brain of those with Rett syndrome. Of note are the observed reductions in the size of the hippocampus and the cortical speech areas. There is less dendritic branching between the layers, meaning that that trans-cortex communication is limited. This being the case, not every layer or section of the brain is affected by the reduction in dendritic branching. For instance, the occipital neurons are less affected and are generally functional. The entire neuroendocrine system is fully functional, as well. These observations seem to contradict any theory that the overall reduction in early brain development is the cause for Rett syndrome.

In a study conducted by Armstrong, Deguchi, & Anytallfy in 2003, researchers theorized that girls with Rett syndrome would present with a random X inactivation in brain tissue, and, as a result, would show the MECP2 mutation in only half of their cells. This hypothesis was not proven in their study, as they observed that this was only the case in certain neurons, but not all. This seems to provide further proof that only certain lobes of the brain are affected by MECP2 mutations.

A later study conducted by Kishi & Macklis determined that young mice with a brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mutation showed reduced dendritic complexity at 3 months, which is the same time that mice with the MECP2 mutation show a reduction in brain volume. Other recent studies show evidence that the reduction in brain size is related to dendritic retraction, indicating that the neurons are actually regressing in maturity in mice with the BDNF mutation. This may imply that mice with the BDNF mutation have similar brain morphology as those with the MECP2 mutation, such as a smaller neocortex and decreased dendritic function. With both mutations showing related phenotypes, is is possible that a dysregulation of BDNF can be the cause of some of the symptoms of Rett syndrome (Kishi & Macklis, 2004).

References

Armstrong, D. D., Deguchi, K., & Antallfy, B. (2003). Survey of MeCP2 in the Rett Syndrome andthe Non–Rett Syndrome Brain. Journal of Child Neurology; 18(10), 683-687.

Kishi, N., & Macklis, J. D. (2004). MECP2 is progressively expressed in post-migratory neurons and is involved in neuronal maturation rather than cell fate decisions. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience; 27(3), 306-321.

Mayo Clinic. (2022, 05 03). Rett Syndrome. Retrieved from Mayo Clinic: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/rett-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20377227

Neul, J. L., & Eskind, A. S. (2023, 03 15). Rett Syndrome. Retrieved from National Organization for Rare Disorders: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/rett-syndrome/

Leave a comment