Abstract:

Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) is a virus that infect a large portion of the population. The virus begins with a primary infection to the epithelial mucosa, then it migrates into neural cells where it lies dormant until stress, dietary changes, or a compromised immune system cause a resurgent infection. The most effective pharmaceutical treatment for HSV-1 is acyclovir, which was discovered in 1977. There have been several advancements in the treatment of HSV-1 since then, but they generally involve newer iterations of the same drug. HSV-1 is also known to cause a host of secondary diseases, such has herpes stromal keratitis, herpes simplex encephalitis, and other somatic infections. There is evidence that HSV-1 is strongly related to Alzheimer’s disease, which has also had very few research breakthroughs in decades. As infectious as HSV-1 is, it can be genetically engineered to target cancer cells, as shown in several recent studies throughout the world. HSV-1 is the only FDA and ESA-approved oncolytic virus. Future research involving herpes could have profound implications for the rest of the medical world.

Introduction:

Viruses are ubiquitous non-living organisms that reside within every living organism. They can cause diseases, disrupt social behaviors, and can even change DNA. They will inject their genetic material into a host cell and hijack its nucleus for replication. Viral replication occurs until the host cell can burst open, spilling viral particles out into the organism, and giving the virus access to even more target cells (de Chadarevian and Raffaetà, 2021).

For humans, several viruses are understood to be present in the majority of the population. Herpes simplex virus comes in several different forms. Most common are HSV-1, HSV-2, and HSV-3. These three versions of the virus are known to cause many different diseases in humans such as cold sores, genital herpes, and chickenpox, respectively. Each of these main diseases can lead to further diseases such as shingles in old age, or herpes keratitis. Some of these secondary diseases can be quite problematic, as HSV is incurable. Another troubling problem with herpes is its ability to infect other parts of the body. For instance, HSV-1, which causes cold sores, can cause a herpes infection of the genitals, which is predominantly caused by HSV-2 (Zhu and Viejo-Borbolla, 2021).

The infection of HSV begins with the attachment of surface glycoproteins to a cell’s plasma membrane via receptors called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). Upon attachment, fusion occurs of the viral and cellular membranes and some of the viral proteins make their way to the cell’s nucleus. Those proteins will mediate the transport of the viral capsid directly to the nucleus. Once the capsid makes it to the nucleus, the viral genome is transported into the nucleus via a nuclear pore. The viral proteins hijack the cell’s RNA polymerase II and begin the process of viral replication (Zhu and Viejo-Borbolla, 2021).

The first, or primary infection, occurs in epithelial cells. Rampant viral replication is met with inflammation and blisters caused by the body’s immune response. This is called the lytic phase of the infection. HSV-induced polarization of infected cells has been observed under which, non-infected cells are attracted to infected cells by a currently unknown mechanism. Following replication in the epithelial cells, the virus will find its way to free nerve endings in the area and undergoes retrograde transport along the axonal nerve endings. There, it will undergo limited replication for a time, until reactivation occurs. This is known as the latent phase of the virus.

While HSV-1 lies dormant in the peripheral nerves, it is not undergoing much active replication. Triggers such as a compromised immune system, or dietary additives can cause the virus to leave its hiding place and it begins to undergo a more rapid replication phase, called the lytic phase. There can be symptoms present before the eruption of any viral lesions. These symptoms can include tingling, burning, itching, and tickling sensations. This is known as the prodromal phase of the virus. Person-to-person transmission occurs via direct contact during either phase of the virus. This usually requires prior epithelial damage due to friction or abrasion of some sort (Zhu, Viejo-Borbolla, 2021).

It is estimated that HSV-1 can be found in over 67 percent of the world’s population (Zhu and Viejo-Borbolla, 2021). Not all of those who have the virus present in their bodies experience manifestations of the virus in the form of the disease. It is not known why, however, it is theorized there is a genetic component to one’s immunity to herpes (Rujescu, et al., 2020). HSV-2 is estimated to be present in over 13 percent of the human population worldwide. As a matter of perspective, herpes zoster (HSV-3) is the virus that causes the disease known as chickenpox. Later in life, this same disease causes shingles infections, for which there is a recent vaccine available.

HSV-1 typically lies dormant in the peripheral nerves around the lips and mouth. Viral particles have been discovered in the trigeminal ganglion, deep within the cranium (Patil, et al., 2022). Viral particles have also been discovered in the brain tissue of cadavers from patients who suffered from Alzheimer’s disease (Itzhaki, 2021). It has been theorized that the virus can make its way into the brain and cause an inflammatory response that creates plaques and tangles within the neurons of the brain, leading to the exacerbation of Alzheimer’s symptoms (Itzhaki, 2021).

Medications for HSV-1 are limited and can be expensive. It can be difficult to treat, as the virus characteristically lies dormant in peripheral nerves until triggered. In the dormant phase, there is very little viral replication taking place. Only when the virus enters the lytic phase is it accessible to medications. Current treatments for HSV-1 in the United States predominantly consist of varying applications of antivirals. The most prevalent antiviral for the treatment of HSV-1 is acyclovir. Acyclovir can be used in a topical form and as oral medication. Penciclovir is similar in potency against HSV-1, and can also be prescribed in a topical or oral form. Some over-the-counter medications can be effective at reducing the healing time of herpes lesions, however, they are expensive and not effective in blocking viral replication. Recent studies have determined that supplementation of vitamin D and L-lysine can also be an effective treatment for HSV-1.

The most prescribed treatment for HSV-1 is the antiviral drug, acyclovir. It can be prescribed in a topical ointment form or an oral tablet. Acyclovir has been proven to stop viral replication and shorten the healing time of viral lesions (Fiddian, et al., 1983). In its topical form, acyclovir can be applied directly to lesions or blisters as soon as prodromal symptoms are experienced for best results. As effective as they can be, topical ointments are not ideal. There is low transdermal permeability, which calls for a large dose to be administered. Topical acyclovir ointments can contain anywhere from 1-5% acyclovir but most of that is not administered onto viral particles and is lost in some way or another.

In 1983, researchers performed the first randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study that had been performed to test the efficacy of topical acyclovir for the treatment of oral herpes. Prior to this study, oral acyclovir had been proven effective for the treatment of genital herpes in other studies. Topical acyclovir, however, had not been measured as an effective treatment (Fiddian, et al., 1983).

Citing poor transdermal penetration of the drug, researchers chose to formulate a cream with 5% acyclovir dissolved with dimethyl sulfoxide, based on the suggestion that it would be a more effective vector for the application of the drug. The experimental subjects were chosen from a pool of five thousand employees at a petroleum plant. Ninety subjects were chosen after they self-reported recurrent oral herpes lesions. The subjects were randomly sorted into two groups and were given a 10-gram tube of either acyclovir cream, or a similar placebo cream (Fiddian, et al., 1983).

The pool of subjects was reduced from 90 to 55 after various disqualifying events and the 55 remaining subjects were re-randomized for a second round of the trial. In total, 74 infections were documented and the result was significantly better for the acyclovir group than the control group. A significant flaw in this trial was that so many test subjects were lost due to scheduling conflicts and the simultaneous use of other medications while undergoing the trial. The researchers were extremely thorough in their randomization, which accounted for most potential flaws (Fiddian, et al., 1983).

Oral acyclovir can be prescribed in two primary doses. A daily 500 mg dose as a prophylactic against potential eruptions can be prescribed for those who are prone to common lesions. Otherwise, acyclovir can be prescribed on an as-needed basis, wherein a patient will take an extremely large dose to stop the virus in its tracks. This is an effective strategy against HSV-1, however, can be problematic for the patient. The dose in this case is 4 grams of acyclovir tablets. Taking all 4 grams at once can cause damage to the liver, so it has to be split up into two 2-gram doses, spread apart by twelve hours. Acyclovir is an effective treatment but it is not ideal to take or apply such large doses at once. Penciclovir is another antiviral medication that is commonly prescribed for the treatment of herpes. It can be prescribed by the same modalities as acyclovir, and at the same concentrations. Both penciclovir and acyclovir act by preventing viral replication. These medications are extremely effective, especially if taken (Brunton, et al., 2018).

Over-the-counter (OTC) treatments can be effective at reducing the healing time of lesions but there is no evidence that any OTC medications can stop viral replication. The only FDA-approved medication is docosanol. Docosanol is typically found in a 10% cream. Docosanol’s mechanism of action is unique to that of acyclovir and penciclovir, as it prevents HSV-1 glycoproteins from entering the plasma membrane of epithelial cells. This can be an effective strategy against HSV-1 in that it can prevent the further spread of the virus during the lytic phase, reducing the healing time of lesions (Treister and Woo, 2010).

Vitamin supplementation has proven helpful in the treatment of HSV-1. A recent study presented a treatment protocol for recurrent herpes labialis involving a low-end dosage of l-lysine supplements. In this context, l-lysine is an essential amino acid that counteracts the action of arginine, which is used in the virus’ replication process. With the supplementation of l-lysine, one can counteract the replication of the virus. A safe dosage of l-lysine stays within the range of 0.5-3g. A dose any higher than 3g can cause gastrointestinal symptoms.

This study followed 12 subjects over the course of eight years. Subjects were prescribed a small dosage of 500mg l-lysine which was to be taken prophylactically. They were also educated on how to avoid triggering lesions by avoiding excessive sunlight and eating a diet low in arginine, while high in l-lysine. The subjects were contacted intermittently to report symptoms and several outbreaks. After eight years, this resulted in a significant reduction in the number and severity of outbreaks experienced by study participants.

This study had a very small sample size of twelve subjects. To obtain statistically significant data, they should follow up with a larger sample size. The method of collecting data was very subjective, as the subjects were just spoken to on the phone. The l-lysine also cannot be fully attributed to the reduction in severity and frequency of outbreaks, as the subjects were coached on how to avoid outbreaks altogether. There was a significant amount of research that went into the choice of dose, and there were many referenced studies that provided similar results (Pedrazini, et al., 2018).

Future treatments for HSV-1:

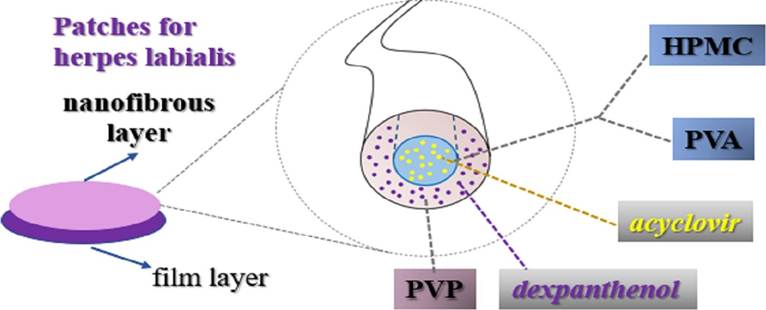

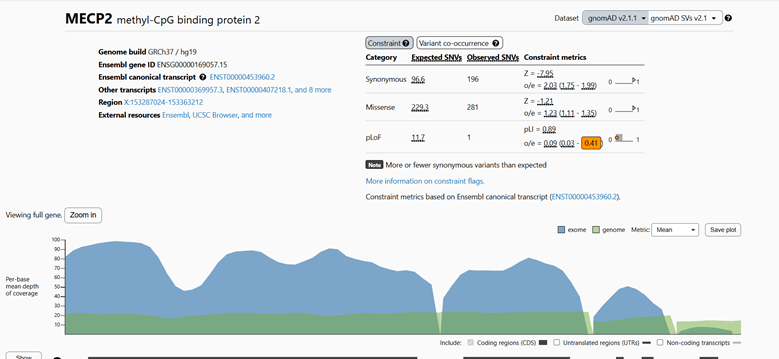

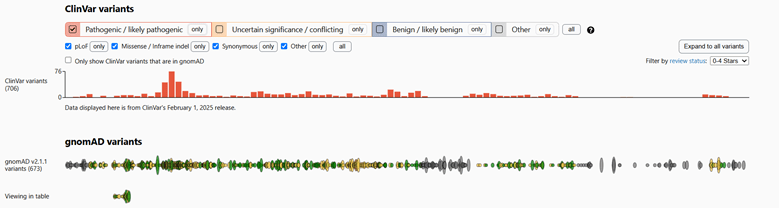

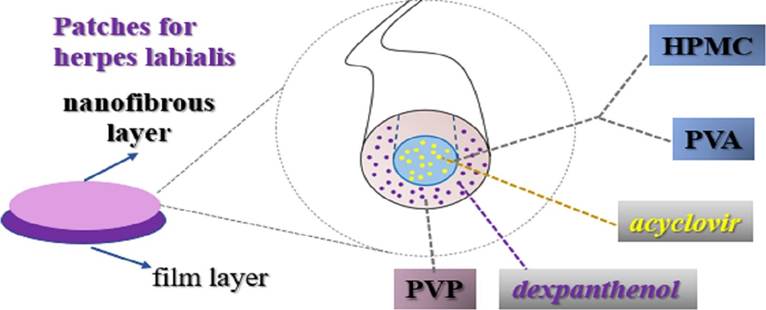

To create a more effective treatment for HSV-1, researchers have devised a technique to create nanofiber patches that could be loaded with antiviral medications, such as acyclovir or penciclovir. The fibers would have a flexible, porous outer shell, and a medicated core (Figure 3). The project sought to manufacture several iterations of these fibers with varying core materials, then the fibers were closely examined with several high-quality imaging techniques to ensure the proper functionality of the structure of the fibers. Once the desired structures were confirmed, the patches were tested for their antiviral capabilities against human embryonic lung cells infected by the virus. This antiviral capability was tested against a common commercially available cream, Zovirax. The test resulted in a positive outcome wherein the fibers were able to release 100% of their medication in just over thirty minutes. The antiviral activity was also measuredly higher than that of Zovirax cream (Kazsoki, et al., 2022).

The strength of this project lies in the thoroughness of the design. Several iterations of the patches were manufactured and subsequently tested on human cells. Unfortunately, one of their manufacturing techniques was not successful, as it seemed to microscopically explode during the manufacturing process. As thorough as this project is, the question remains as to whether or not these patches would be effective in practice. The tests were done in the lab under strict conditions, using human embryonic lung cells. The targeted HSV-1 virus is not typically found in human lung cells, which have a different morphology from human epithelial cells.

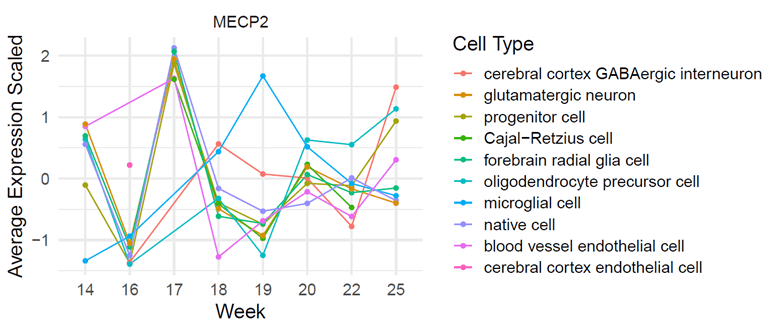

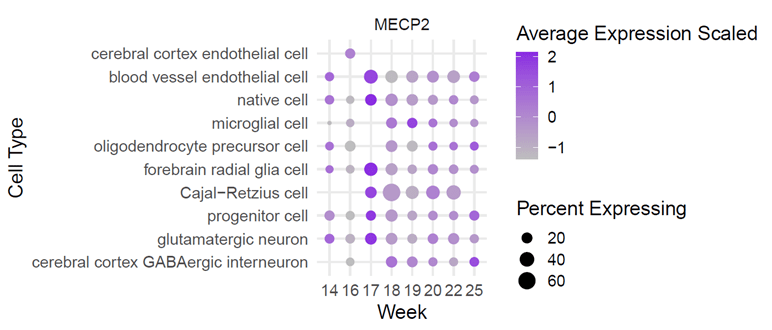

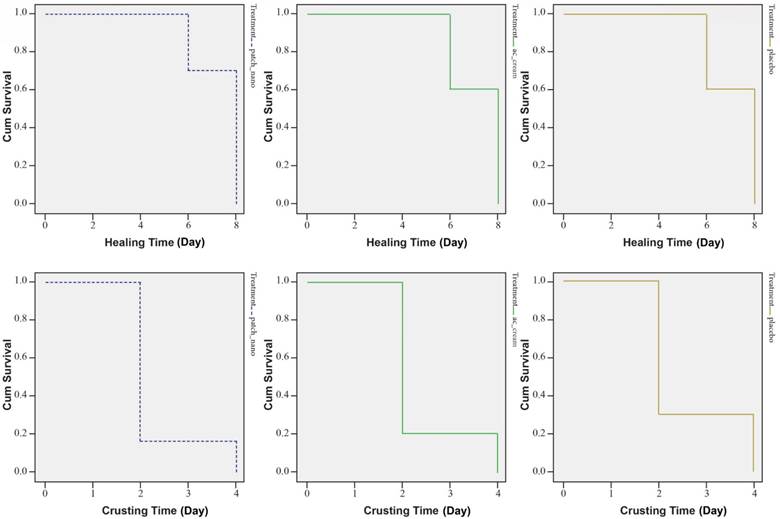

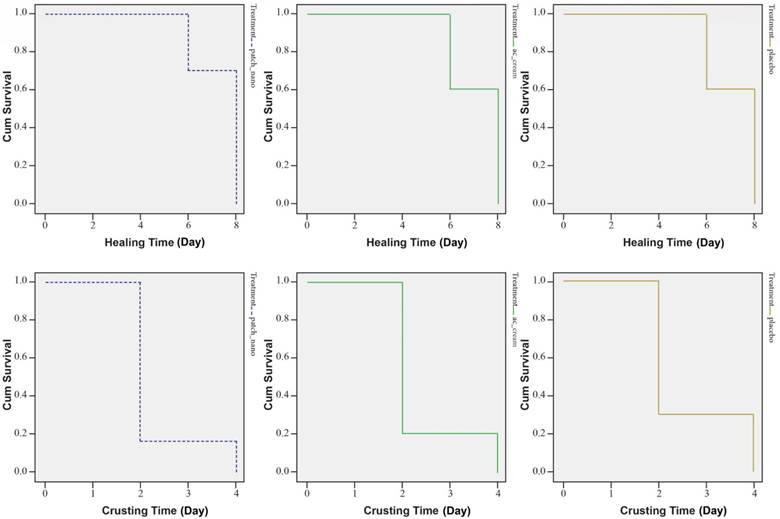

A further study (Golestannejad, et al., 2021) was devised to investigate the effectiveness of the acyclovir-core nanofiber patches on living human subjects. Sixty participants who suffer from recurring herpes labialis were chosen for this trial. Participants were randomly split into three groups of twenty. One group was treated with the acyclovir nanofiber patches, another group was treated with traditional topical acyclovir, and the third group was treated with a placebo nanofiber patch. Subjective pain symptoms were recorded using input from the subjects. Objective healing time and crusting time were recorded by the researchers using a pre-determined scale. The study resulted in a non-significant change in the healing and crusting time of the sores (Figure 4).

Theoretically, the nanofiber patches should provide a more effective vector for the application of acyclovir cream. The effective surface area is vastly larger and should provide a vastly larger amount of medication to a more targeted area. The researchers in this study were not able to capitalize on the inherent benefits of the patches and would need to perform a follow-up study with a larger sample size, and an established metric on the amount of medication that will be administered via the use of these nanofiber patches. More research is required to find a middle ground between the initial study involving nanofiber patches, and the subsequent study (Golestannejad, et al., 2021).

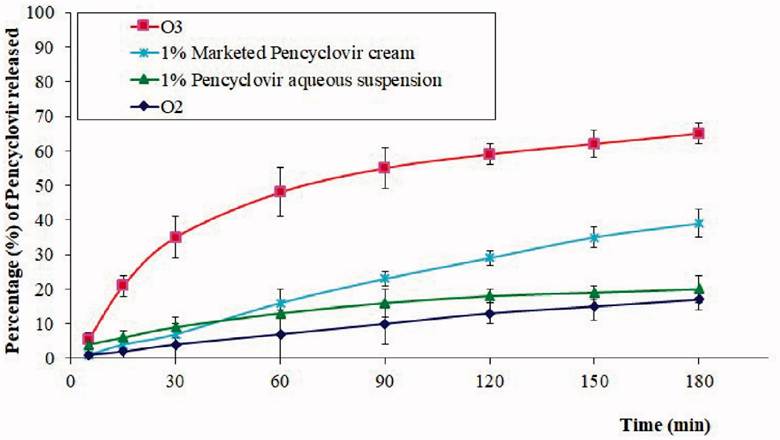

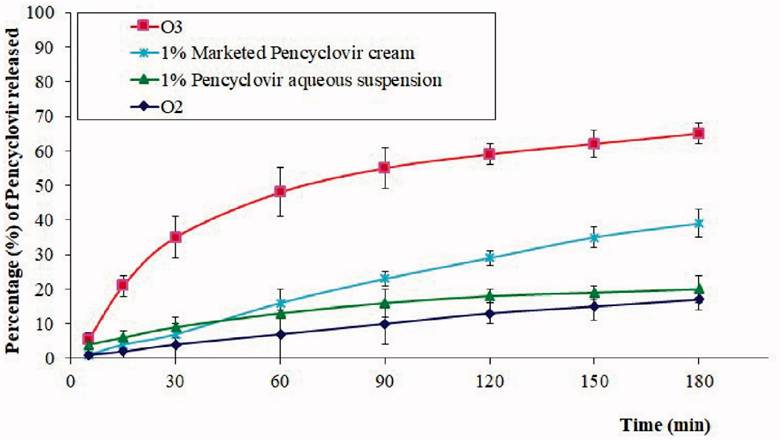

Penciclovir is another of the most common antiviral drugs prescribed to help treat oral herpes. It can help reduce symptoms as well as shorten the healing time of cold sores. As effective as it is at treating oral herpes, it does not have good dermal permeability. Therefore, it needs to be formulated in relatively large dosages for creams and gels to overcome the low permeability. Current research into penciclovir involves the formulation of a penciclovir-loaded gel with better bioavailability and dermal permeability. Researchers have accomplished this by testing many different mixtures of an oil base, a surfactant, a self-nano emulsifying drug delivery system (SNEDDS), and the drug (Hosny, et al., 2021).

Many essential oils were tested for the base, including lavender oil. Lavender oil is proven to have very strong antiviral activity and strong antiseptic properties. The ingredients for each gel were mixed using widely-available lab techniques, such as centrifuges, with a 6:4 ratio of oil and emulsion, along with the SNEDDS and 100mg of the drug. Each formulation was tested for droplet size and permeability. Permeability was tested by applying the gel to cultured buccal cells from sheep. The droplets needed to be large enough to maintain drug stability, and small enough to apply the drug to the cells. This was achieved most sufficiently by using the lavender oil formulation, which significantly outperformed every other formulation (Figure 5) (Hosny, et al., 2021).

Relationship with Alzheimer’s disease:

In 2021, Ruth Itzhaki introduced a review to the publication, Vaccines, in which she emphasizes her earlier work in 2017 which suggested an increased level of investigation into the relationship between HSV-1 and AD. Since her 2017 publication, many researchers took up the call to scrutinize the two diseases in relation to one another (Itzhaki, 2021). Many new and exciting research studies have been designed in the time since. Such studies involve the use of stem cells to create human models of AD (Cairns, et al., 2020; D’Autio, et al., 2019; Abrahamson, et al., 2020). Each of these studies have reinforced the suggestion that there is a strong relationship between HSV-1 and AD, however, none have yet pinpointed the exact mechanism by which these two diseases interact.

The prevailing theory put out by Ruth Itzhaki, herself, is that HSV-1 can cause AD by creating an inflammatory response in the brain which creates more Aβ plaques and the accumulation of which creates a non-conductive environment in the neural cells of the brain. Itzhaki surmises that the occurrence of a neural infection of HSV-1 later in life can increase the chances of an individual developing AD. It has been observed that subjects who present with AD sometimes have HSV-1 in its latent form in their brains (Itzhaki, et al., 1997). It was also observed that patients without AD have shown latent HSV-1 in their brains. It is postulated by Itzhaki that the specific allele for apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) is present in patients with AD who presented with a strong reactivation of latent HSV-1 in their brains later in life. This allele is widely theorized to be the largest single factor in predicted a person’s risk for developing AD (NIH, 2023).

Itzhaki also notes that there is a wealth of clinical evidence showing that the treatment of a herpes-related virus prior to the onset of dementia or AD decreases the risk of developing symptoms. For recent subjects who have received the shingles vaccine to prophylactically prevent a recurrence of the varicella zoster virus (VZV), there is a statistically significant reduction in risk of developing dementia symptoms later in life (Cairns, et al., 2022). Additionally, one who is treated with daily valacyclovir (VCV) will also show a reduction in risk of developing dementia-related symptoms.

This phenomenon could be due to Itzhaki’s theory that the virus, itself is causing AD but there could be another correlation that the researchers are not seeing. For instance, there could be another neural virus that has not yet been detected, but is treatable with the same antivirals as HSV-1. There could be many explanations for these correlations, but more research will need to be performed to find the necessary mechanisms behind the relationship.

There are several genes associated with the development of AD, but the APOE4 gene seems to be the most prevalent of them. The APOE4 gene is also associated with the development of cold sores. There is no indication that having the APOE4 gene increases one’s risk for infection with HSV-1, however, subjects who do have the APOE4 gene and are infected with HSV-1 are more likely to present with cold sores (Itzhaki, 2022). This observation seems to imply that the presence of the APOE4 gene increases the clinical manifestations of the virus, while, in others without the gene, clinical manifestations of the virus are less likely. This explains why around 80% of most populations are infected with HSV-1, but only a small percentage of those subjects present with cold sores (Itzhaki, 2022). It is estimated that somewhere between 15-25% of the population carries at least one allele for APOE4, but not all of those people develop AD, or HSV-1 (NIH, 2023).

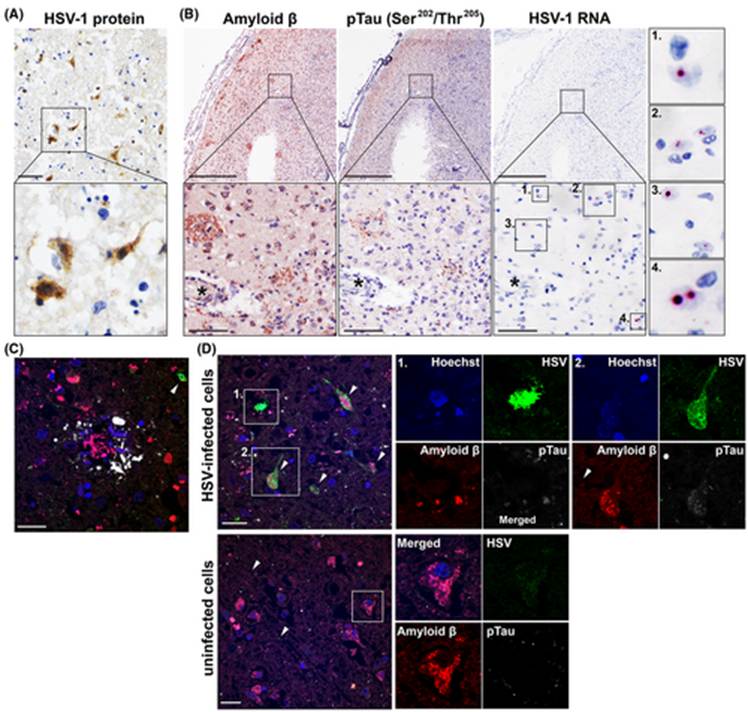

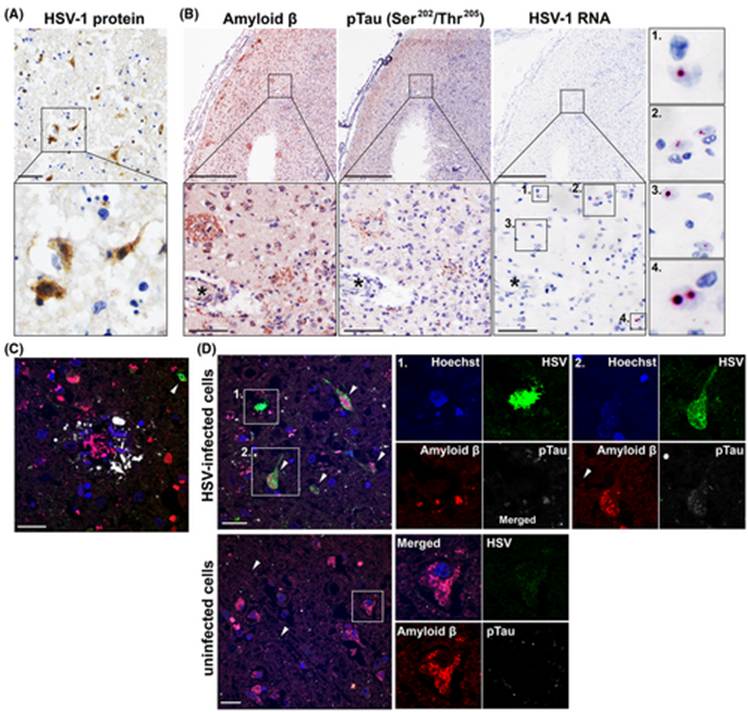

The scientific community is well-aware that HSV-1 can infect the brain, such is the case with herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) (Patil, et al., 2022). In order to test the correlation between HSV-1 and AD, a study was conducted in 2021 by Tran, et al. Few pathogens can pass through the blood-brain barrier. HSV-1 can pass through the blood-brain barrier and infect neural tissue. The researchers in this study sought to determine the extent to which HSV-1 can contribute to symptoms of AD. When HSV-1 infects the brain, it can cause HSE.

The researchers theorized that frequent HSE flare-ups can create more Aβ plaques and NFTs in the brain, creating a typical neural environment that would be seen in a brain infected with AD. The brain samples acquired were all from people who were diagnosed with AD and HSE. The samples were stained and examined for HSV-1 infection. Of the five samples, three showed Aβ plaques (Fig. 6). Two showed NFTs and all had HSE. Through various imaging techniques, the researchers were able to observe the localization of HSV-1 cells around Aβ plaques. Since only three of the five HSE samples had plaques present, it was determined that an active HSE infection is not associated with the exacerbation of AD symptoms.

This study was well-designed and was extremely successful at producing results. The results were not what the researchers would have liked to have seen, however, they were extremely useful in the study of the association between HSV-1 and AD. This is a weakness, as well as a strength of this research.

Not many original questions were answered by this study and there is no conclusive evidence that there is a relationship between HSV-1 and AD, however, this does open the door for future experiments regarding this relationship. The sample size was quite small at five, but this was due to limited resources. The researchers were able to extract as much information as was available from the few samples they were able to acquire. Future studies should be designed to answer some of the open questions left after the completion of this study. The researchers are still unsure of why there are HSV-1 particles localized around Aβ plaques when present. This study was not able to answer the question of correlation between AD and HSV-1, but still created a strong basis for future endeavors into this profound research.

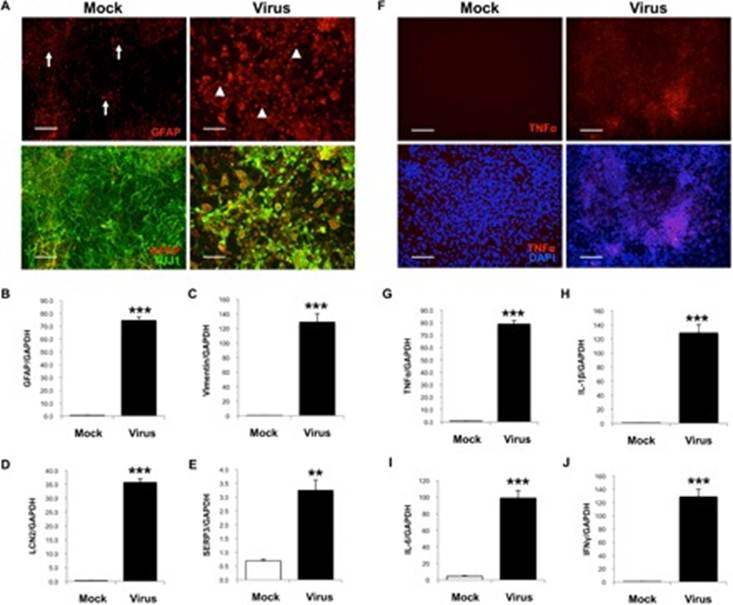

Another study, published in 2020, sought to create a 3d human brain-like model and study the effects of HSV-1 on brain tissue as it relates to Alzheimer’s disease (AD). This study was performed by Cairns, et al. and was based on a specific subset of AD cases. Of the 6 million people in the United States who are infected with AD, 95% are diagnosed with late-onset AD. Approximately 1-6% of cases are classified as early-onset AD (EOAD), in which a patient begins developing the disease under the age of 60 years old. Patients diagnosed with EOAD exhibit the same hallmark symptoms of AD, including the development of β-amyloid plaques (Aβ) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). This form of AD is brought on by mutations in one of three specific genes associated with Aβ production.

Using EOAD as a model for the study is not ideal, as it is only present in 1-6% of AD cases. A workaround developed for this study was to create a 3d brain-like model using human-induced neural stem cells (hiNSCs) which were cultivated using human foreskin fibroblasts. The cultivated cells were then infected with HSV-1 which was titrated and purified to 2×10^7 PFU. After infection, hiNSCs were shown to be highly infectable by HSV-1. The infection of the human-like brain model resulted in increased gliosis and neural inflammation of hiNSCs. Regular treatment with valacyclovir (VCV) produced cell with significantly reduced gliosis and neural damage. This study shows significant evidence that HSV-1 can cause some AD symptoms and can also create Aβ plaques characteristic of AD.

The researchers were extremely thorough in their notation and created an easily replicable study that has promising results. As accurate an analog it is to human brain tissue, the 3d model is not a complete representation of a human subject. Further research on human subjects is needed to determine the effects on living subjects of HSV-1. The analog tissues were also not able to be fully accurate to an AD patient’s tissues. A future study could use proposed aging methods on the tissues in order to more accurately model the brain of an AD patient.

The results of this study suggest that there is a strong case for the treatment of AD by the use of antiviral drugs, such as VCV. Recent trials of the use of the compound, GV971 have shown that the compound reduced neural inflammation and improved cognition in trial subjects (Itzhaki, 2021). Itzhaki believes that the use of a related, sulfated compound, fucoidan, could prove more successful in the treatment of AD. This is due to the substances degree of sulfation, and the inherent antiviral properties of marine polysaccharides, from which the substance is derived. These substances have been observed to reduce the incidence of Aβ plaques, which have been assumed one of the hallmark causes of symptoms of AD.

Originally published in 2006, a study conducted by Lesné, et al. concluded that the presence of Aβ contributed to cognitive decline in middle-aged mice. The study uses mice of several age categories and measures their cognitive abilities, as well as their memory. Researchers then examined the brains of the mice to find accumulations of Aβ plaques, and determined that the plaques were the cause of the decline in cognition with age.

Several figures and images were used in the publication of this report, but one was thrust into question upon observations detected by Matthew Schrag (Pilier, 2022). Schrag noticed that one of the images presented with apparent evidence of tampering. This tampering implies that the research of Lesné, et al. may not have been entirely accurate. It is also worth noting that Lesné’s experiment was not able to be replicated under peer-review by research groups outside of his own laboratory.

If Lesné‘s research was fabricated, then that could suggest that Aβ plaques are not as significant in the causation of symptoms of AD. The apparent tampering of the photo alone does not suggest that the research is unsound. However, if the research is unsound, then that could have contributed to the lack of advancements in the field of AD treatments over the last couple of decades, as most recent research has been designed to treat the symptoms and causes of Aβ plaques.

The use of HSV-1 as an oncolytic virus:

Herpes simplex virus type 1 is the only virus that is approved by the European EMA, and the American FDA as an oncolytic virus (OV). The viral genome is edited to utilize the virus as a directly injectable treatment for tumors. However, the strains used for synthesis are very specific strains normally used for laboratory reference. Talimogene laherparepvec (T-Vec) is the specific strain of HSV-1 that has been approved by the FDA for use as an OV (Koch, et al., 2020). There are several other strains that are being developed and tested against numerous types of cancer cells.

This marvel of modern medicine is achieved by genetically engineering a select strain of the virus to reduce its ability to infect neural cells and increase an immune response. T-Vec, in particular, was engineered by researchers specifically to treat a form of melanoma. To achieve this feat, researchers engineered the viral genome of a specific strain of HSV-1 so that it would present with lower neurovirulence, and augment an immune response. They also inserted a gene that would further augment the immune response (Koch, et al., 2020). The success of T-Vec has proven that HSV-1 can be genetically engineered to treat specific types of cancer. In the wake of this success, many researchers across the world have designed studies and trials using other strain of HSV-1 to treat various types of cancer.

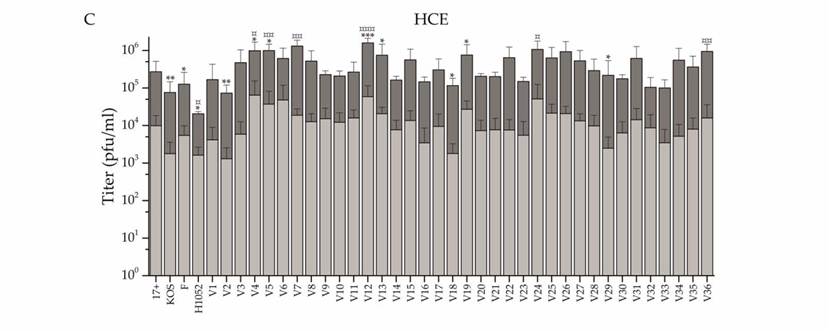

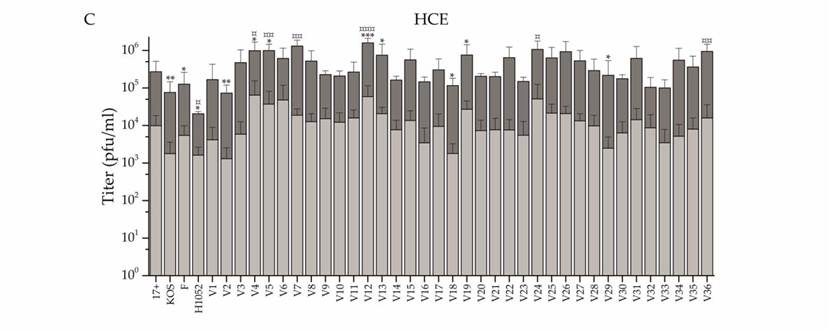

A recent study performed by Kalke, et al. in 2022 tested the efficacy of thirty-six “wild” strains of HSV-1 for use as an OV. Viral cells were lysed using a freeze-thaw cycle. Each of the thirty-six strains was tested for resistance to acyclovir before being tested on human cells. Viral particles were used to infect Normal Human Corneal Epithelial cells (HCE) at 5 plaque-forming units (pfu) per HCE cell. After genome sequencing, the viruses were each tested for oncolytic potential against several types of cancer cells at 2 pfu per cell. The resulting infections successfully reduced the viability of cancer cells in neuroglioma, adenocarcinoma, and lymphoma (Fig. 8). Especially effective was the infection of lymphoma cells, which saw a significant reduction in viability 2 days post-infection from six of the clinical strains of HSV-1 tested.

This study was designed to find new backbones for oncolytic HSV strains (oHSV). The researchers were successful in reducing the viability of test cells representing various forms of cancer. A weakness of this study is that it is somewhat unclear regarding numbers. In some sections, infections were said to have been incubated for two days, in some places four. Additionally, there does not seem to be any clinical explanation for the concentration of viral pfu’s used. Another weakness of this study is that the cancer cells used were extremely limited.

Kalke’s study was able to test many viral strains and prepare them for testing. All strains were acquired regionally in Finland. The researchers performed every test they needed in order to prove that their strains were viable as oncolytic viruses. In the future, researchers will should seek to perform a full sequencing of the genomes of each strain, rather than just a few sections. Ultimately, the results of this research can be instrumental in the design of future studies involving OVs. With such a vast array or regional variants available, there are many possibilities of which strains to use for specific purposes.

Hematopoietic cells are characteristically resistant to HSV-1 because the infection mechanism of the virus does not typically target blood cells. There have, however, been many cases of the sudden resolution of hematological malignancies following systemic viral infections documented. It is theorized that this is because the systemic viral infection can also infect the cancer cells in a subjects bloodstream due to their differing microbiology from a normal hematological cell.

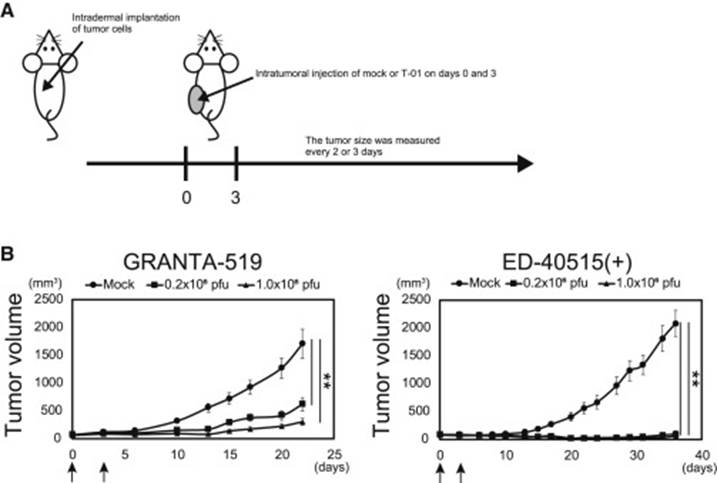

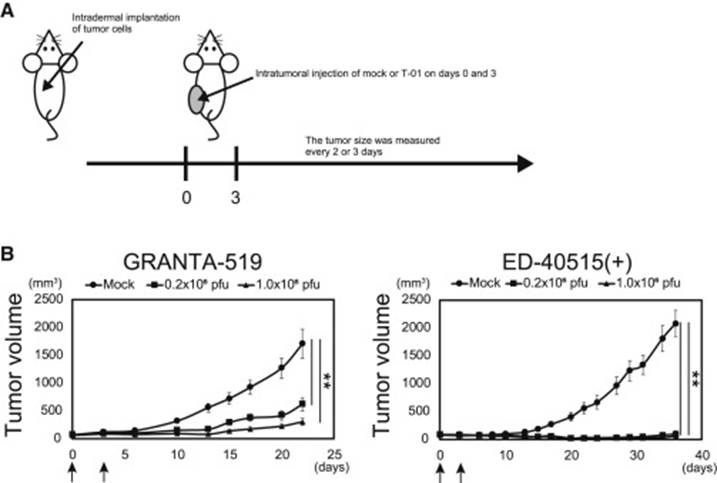

If it is possible for a virus to kill these types of cancer cells, then it is possible to engineer an OV to treat them. Aiming to investigate the efficacy of the usage of HSV-1 as an oncolytic vector for the treatment of such hematological malignancies, a study was designed by Ishino, et al. and published in 2020. The researchers hypothesized that the key factor in the treatment of hematological malignancies was the expression of the nectin-1 receptor on the tumor cells. To test their theory, researchers used human cell lines derived from various hematological malignancies.

The expression levels of the nectin-1 receptor were measured in each cell line. These tumor cells were implanted subdermally into mice on their left and right flanks and were then treated with a mock HSV-1 strain (T-01), and an ultraviolet-deactivated strain of T-01 (Fig. 9). One mouse was treated via direct intratumor injection, while the other was treated without injection. The results showed a clear reduction in tumor growth in the mice who were treated with T-01.

This proves that there is, in fact, a correlation between the expression of the nectin-1 receptor, and the oncolytic capabilities of T-01. This study showed some weaknesses in methods, but also some strengths. The researchers were able to test for many different cancer types. However, the cancers tested were retrieved from patients who had recently relapsed, which could have shown a difference in the genome of the cancer cells. A future trial would have to account for this by acquiring cancer cells from primary infections. There were only a few mice tested and it was a very straightforward approach. Another strength of this study is the extensive genome sequencing performed by the researchers. This provides invaluable information for future research. In the future, these data could be used to design a trial involving the treatment of hematological malignancies in human subjects.

Conclusion:

In my research, I have found that the treatments for HSV-1 have not had any real advancements in the decades since the development of acyclovir. There have been several variants of this medication, but they are all most effective at treating the virus after a primary infection. The ideal treatment for HSV-1 infections is a combination of pharmaceuticals and vitamins to prevent recurrent relapses, and ineffectual topical ointments after the prodromal phase has finished. It is an inefficient way to treat the disease, not to mention expensive for the average consumer.

Without a better preventative treatment, or a cure, victims of the virus are at risk of developing other, more serious, presentations of the virus. HSK is a very serious illness and one of the main causes of blindness in the United States. In order to treat this disease and prevent the most debilitating symptoms, one is forced to take daily acyclovir for the remainder of their lives. A daily acyclovir also just so happens to show a reduction in risk associated with the development of AD.

Alzheimer’s disease is one of the most devastating diseases experiences by families in the United States today. There has been little development in new treatments or cures for AD, as well. More recent research has shown that there is a strong correlation between HSV-1 and AD under various circumstances. Treatment of HSV-1 can reduce the risk of developing symptoms of AD. HSV-1 viral particles have been observed in close proximity to Aβ plaques, which are one of the hallmark signs of AD. There is a profound potential here to save millions of families the from the heartache of being forced to watch a loved one’s AD symptoms slowly increase in severity. Further research into this relationship should be a high priority for labs across the world.

Another disease that has no true cure and plagues families every day is cancer. There are as many unique types of cancer as there are unique strains of HSV-1. The most prevalent treatment today is a systemic poison that has horrible, long-lasting side effects. With the development and use of HSV-1 oncolytic viruses, we could potentially treat many different types of cancer with a direct infection that could wipe out the tumor cells altogether. Current trials involve the use of an oncolytic virus injected directly into tumors once every two weeks. The OV is genetically engineered to infect the tumor cells, and not the neural cells of the host, reducing the risk of side effects to the patient. This could prove to be a cheaper, safer alternative to the current chemotherapy treatments used in clinics around the world.

What this research shows is that there is a profound need for more investigation into the HSV-1 virus for various reasons. HSV-1 is a ubiquitous virus that shows up on all corners of the Earth and infects every rung of society. Historically, it has not been thought to cause any significant long-term effects, but recent research shows that this is untrue. Further research into the virus and its uses could prove invaluable to a society plagued with incurable diseases, such as cancers. If we can learn to truly understand this ancient virus, we could unlock a cheat code to cure other diseases, as well as prevent the diseases caused by the virus.

References:

Abrahamson, E. E., Zheng, W., Muralidaran, V., Ikonomovic, M. D., Bloom, D. C., Nimgaonkar, V. L., & D’Aiuto, L. (2021). Modeling Aβ42 Accumulation in Response to Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Infection: 2D or 3D? Journal of Virology, 95(5)10.1128/JVI.02219-20

Adams, Alex J., Klepser, Michael E. (2020). Pharmacy-Based Assessment and Management of Herpes Labialis (Cold Sores) with Antiviral Therapy . Innovations in Pharmacy, 11(3), 1-6. 10.24926/iip.v11i3.1532

Alzheimer’s disease genetics: fact sheet (2004). . National Institute on Aging.

Bodur, M., Toker, R. T., Özmen, A. H., & Okan, M. S. (2021). Facial colliculus syndrome due to a herpes simplex virus infection following herpes labialis. Turkish Journal of Pediatrics, 63(4), 727-730. 10.24953/turkjped.2021.04.023

Cairns, D. M., Itzhaki, R. F., & Kaplan, D. L. (2022). Potential Involvement of Varicella Zoster Virus in Alzheimer’s Disease via Reactivation of Quiescent Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 88(3), 1189-12. 10.3233/JAD-220287

Cairns, D. M., Rouleau, N., Parker, R. N., Walsh, K. G., Gehrke, L., & Kaplan, D. L. (2020). A 3D human brain–like tissue model of herpes-induced Alzheimer’s disease. Science Advances, 6(19), eaay8828. 10.1126/sciadv.aay8828

Cunningham, A., Griffiths, P., Leone, P., Mindel, A., Patel, R., Stanberry, L., & Whitley, R. (2012). Current management and recommendations for access to antiviral therapy of herpes labialis. Journal of Clinical Virology, 53(1), 6-11. 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.08.003

D’Aiuto, L., Bloom, D. C., Naciri, J. N., Smith, A., Edwards, T. G., McClain, L., Callio, J. A., Jessup, M., Wood, J., Chowdari, K., Demers, M., Abrahamson, E. E., Ikonomovic, M. D., Viggiano, L., De Zio, R., Watkins, S., Kinchington, P. R., & Nimgaonkar, V. L. (2019). Modeling Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Infections in Human Central Nervous System Neuronal Cells Using Two- and Three-Dimensional Cultures Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Journal of Virology, 93(9)10.1128/JVI.00111-19

de Chadarevian, S., & Raffaetà, R. (2021). COVID-19: Rethinking the nature of viruses. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, 43(1), 2. 10.1007/s40656-020-00361-8

Fiddian, A. P., Yeo, J. M., Stubbings, R., & Dean, D. (1983). Successful treatment of herpes labialis with topical acyclovir. Bmj, 286(6379), 1699-1701. 10.1136/bmj.286.6379.1699

Golestannejad, Z., Khozeimeh, F., Mehrasa, M., Mirzaeei, S., & Sarfaraz, D. (2022). A novel drug delivery system using acyclovir nanofiber patch for topical treatment of recurrent herpes labialis: A randomized clinical trial. Clinical and Experimental Dental Research, 8(1), 184-190. 10.1002/cre2.512

Hosny, K. M., Sindi, A. M., Alkhalidi, H. M., Kurakula, M., Alruwaili, N. K., Alhakamy, N. A., Abualsunun, W. A., Bakhaidar, R. B., Bahmdan, R. H., Rizg, W. Y., Ali, S. A., Abdulaal, W. H., Nassar, M. S., Alsuabeyl, M. S., Alghaith, A. F., & Alshehri, S. (2021). Oral gel loaded with penciclovir-lavender oil nanoemulsion to enhance bioavailability and alleviate pain associated with herpes labialis. Drug Delivery, 28(1), 1043-1054. 10.1080/10717544.2021.1931561

Ishino, R., Kawase, Y., Kitawaki, T., Sugimoto, N., Oku, M., Uchida, S., Imataki, O., Matsuoka, A., Taoka, T., Kawakami, K., van Kuppevelt, T. H., Todo, T., Takaori-Kondo, A., & Kadowaki, N. (2021). Oncolytic Virus Therapy with HSV-1 for Hematological Malignancies. Molecular Therapy, 29(2), 762-774. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.09.041

Itzhaki, R. F. (2021). Overwhelming Evidence for a Major Role for Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 (HSV1) in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD); Underwhelming Evidence against. Vaccines (Basel), 9(6), 679. 10.3390/vaccines9060679

Itzhaki, R. F., Lin, W., Shang, D., Wilcock, G. K., Faragher, B., & Jamieson, G. A. (1997). Herpes simplex virus type 1 in brain and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet (British Edition), 349(9047), 241-244. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)10149-5

Iwanaga, J., Fukuoka, H., Fukuoka, N., Yutori, H., Ibaragi, S., & Tubbs, R. S. (2022). A narrative review and clinical anatomy of herpes zoster infection following COVID‐19 vaccination. Clinical Anatomy (New York, N.Y.), 35(1), 45-51. 10.1002/ca.23790

Kalke, K., Orpana, J., Lasanen, T., Esparta, O., Lund, L. M., Frejborg, F., Vuorinen, T., Paavilainen, H., & Hukkanen, V. (2022). The In Vitro Replication, Spread, and Oncolytic Potential of Finnish Circulating Strains of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1. Viruses, 14(6), 1290. 10.3390/v14061290

Kazsoki, A., Palcsó, B., Alpár, A., Snoeck, R., Andrei, G., & Zelkó, R. (2022). Formulation of acyclovir (core)-dexpanthenol (sheath) nanofibrous patches for the treatment of herpes labialis. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 611, 121354. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.121354

Kim, H., Kang, K. W., Kim, J., & Park, M. (2022). Uncommon cause of trigeminal neuritis and central nervous system involvement by herpes labialis: a case report. BMC Neurology, 22(1), 1-294. 10.1186/s12883-022-02823-x

Koch, M. S., Lawler, S. E., & Chiocca, E. A. (2020). HSV-1 Oncolytic Viruses from Bench to Bedside: An Overview of Current Clinical Trials. Cancers, 12(12), 3514. 10.3390/cancers12123514

Öztekin, A., & Öztekin, C. (2019). Vitamin D Levels in Patients with Recurrent Herpes Labialis. Viral Immunology, 32(6), 258-262. 10.1089/vim.2019.0013

Patil, A., Goldust, M., & Wollina, U. (2022). Herpes zoster: A Review of Clinical Manifestations and Management. Viruses, 14(2), 192. 10.3390/v14020192

PEDRAZINI, M. C., ARAÚJO, V. C., & MONTALLI, V. A. M. (2018). The effect of L-Lysine in recurrent herpes labialis: pilot study with a 8-year follow up. RGO – Revista Gaúcha De Odontologia, 66(3), 245-249. 10.1590/1981-863720180003000083517

Pilier, C. (2022). BLOTS ON A FIELD? A neuroscience image sleuth finds signs of fabrication in scores of Alzheimer’s articles, threatening a reigning theory of the disease. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science), 377(6604), 358. https://www.science.org/content/article/potential-fabrication-research-images-threatens-key-theory-alzheimers-disease

Ramalho, K. M., Cunha, S. R., Gonçalves, F., Escudeiro, G. S., Steiner-Oliveira, C., Horliana, A. C. R. T., & Eduardo, C. d. P. (2021). Photodynamic therapy and Acyclovir in the treatment of recurrent herpes labialis: A controlled randomized clinical trial. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy, 33, 102093. 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.102093

Rujescu, D., Herrling, M., Hartmann, A. M., Maul, S., Giegling, I., Konte, B., & Strupp, M. (2020). High-risk Allele for Herpes Labialis Severity at the IFNL3/4 Locus is Associated With Vestibular Neuritis. Frontiers in Neurology, 11, 570638. 10.3389/fneur.2020.570638

Silva-Alvarez, A. F., de Carvalho, A. C. W., Benassi-Zanqueta, É, Oliveira, T. Z., Fonseca, D. P., Ferreira, M. P., Vicentini, F. T. M. C., Ueda-Nakamura, T., Pedrazzi, V., & de Freitas, O. (2021). Herpes Labialis: A New Possibility for Topical Treatment with Well-Elucidated Drugs. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 110(10), 3450-3456. 10.1016/j.xphs.2021.06.029

Tran, D. N., Bakx, A. T. C. M., van Dis, V., Aronica, E., Verdijk, R. M., & Ouwendijk, W. J. D. (2021). No evidence of aberrant amyloid β and phosphorylated tau expression in herpes simplex virus-infected neurons of the trigeminal ganglia and brain. Brain Pathology (Zurich, Switzerland), 32(4), e13044-n/a. 10.1111/bpa.13044

Treister, N. S., & Woo, S. (2010). Topical n-docosanol for management of recurrent herpes labialis. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 11(5), 853-860. 10.1517/14656561003691847

Wang, L., Wang, R., Xu, C., & Zhou, H. (2020). Pathogenesis of Herpes Stromal Keratitis: Immune Inflammatory Response Mediated by Inflammatory Regulators. Frontiers in Immunology, 11, 766. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00766

Zhu, S., & Viejo-Borbolla, A. (2021). Pathogenesis and virulence of herpes simplex virus. Virulence, 12(1), 2670-2702. 10.1080/21505594.2021.1982373

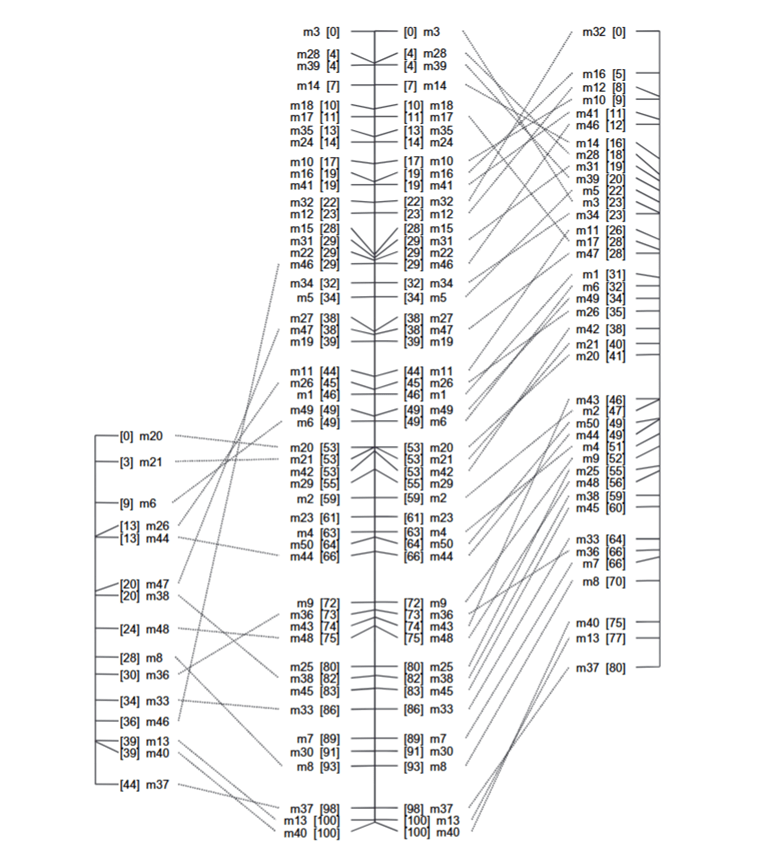

Appendix:

Figure 1: Herpes virion containing a large, double-stranded DNA genome contained and protected by a capsid, which is surrounded by a tegument layer. The envelope contains glycoproteins which are used to attach to host cells and release genetic material. (Zhu and Viejo-Borbolla, 2021).

Figure 2: HSV cell cycle. 1: Viral glycoproteins bind to receptors on the cell plasma membrane. 2: The viral capsid fuses with the plasma membrane of the cell. 3: Viral capsid and proteins from the integument are transported to the cell nucleus via microtubules. 4, 6, 9: Transcription of the viral genome takes place in the cell nucleus. 5, 7, 10: Translation of the viral genome. 8: Viral DNA replication. 11: Replicated viral DNA undergoes encapsidation. 12: Capsid is transported through the cytoplasm. 13: Vesicles transport the capsid to the plasma membrane 14: Viral capsid exits the cell (Zhu and Viejo-Borbolla,2021).

Figure 3: Acyclovir core, PVP sheath nanofiber used to create medicated patches. Acyclovir hydrochloride and dexpanthenol were used as active pharmaceutical ingredients. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) were used as the precursor solutions for formulation. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) was used to formulate the shell (Kazsoki, et al., 2022).

Figure 4: Survival curves of crusting and healing time in subjects’ lesions. Groups from left to right are acyclovir nanofiber patches, topical acyclovir, and placebo. The mean crusting time for each group, respectively was 2.3, 2.4, and 2.6 days. the mean healing time was 7.4, 7.7, and 7.2 days, respectively (Golestannejad, et al., 2021).

Figure 5: Percentage of acyclovir released per minute with differing application vectors. O2: chitosan hydrogel loaded with PV powder, O3: chitosan hydrogel loaded with optimized PV-LO SNEDDs , 1%: PV cream, and 1% PV aqueous suspension (Hosny, et al., 2021).

Figure 6: Various imaging techniques showing the proximity of HSV infected cells to Aβ plaques. Proteins are stained with immunohistochemistry (IHC) A: Brain sample stained for HSV proteins. B: Consecutive samples showing staining for pTau and Aβ proteins. C, D: samples stained with immunofluorescence for HSV, pTau, Aβ. Cell nuclei are stained in blue, HSV proteins are stained green, Aβ is red, and pTau is white. These images prove the spatial correlation between HSV1 and AD signs (Tran, et al., 2021).

Figure 7: Immunostaining images showing that HSV-1 infected mock-brain cells exhibit reactive gliosis and inflammation. A, B: hiNSCs infected with HSV-1 showing signs of neuroglial activity, indicative of gliosis. C-J: Several other inflammatory markers present in cases of AD are found in hiNSCs infected with HSV-1 (Cairns, et al., 2020).

Figure 8: Graph showing the intracellular and extracellular titers of each clinical isolate. HCE cells were infected at 0.1 pfu/cell and titers were measured at pfu/ml. Each of the 36 clinical isolates were tested and the light grey bars show the extracellular viral titer measured. The dark grey bar shows the intracellular titer, which is consistently much higher than the extracellular titers. This shows the high intracellular virulence of the virus.

Figure 9: Anti-tumor effects of test mice. A: The treatment plan for the mice. B: growth curve of tumors after treatment. The arrows mark the dates of the injections on day 0 and day 3. The size of each tumor was measured every 2-3 days.