Rett syndrome (RTT) is a severe neurodevelopmental disorder primarily affecting women, caused mainly by mutations located on the MECP2 gene found on the X chromosome (Merritt, 2020). MECP2 is a gene that encodes the methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2), a regulator of gene expression in the brain. MeCP2 binds to methylated DNA sequences, impacting the activity of numerous genes that are sed in neuronal development and function (Chahrour & Zoghbi, 2007). Understanding the types of mutations in MECP2 that cause RTT, compared to those found in the general population, can provide insight into how genetic variations can lead to different outcomes.

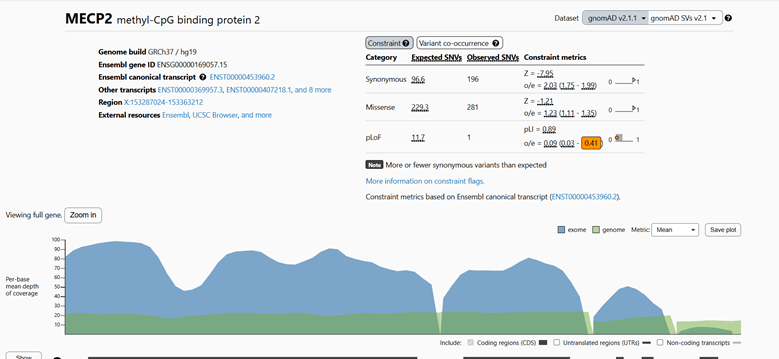

Genetic testing confirming an MECP2 mutation helps diagnose Rett syndrome. The mutations responsible for RTT are typically those that severely disrupt the function or production of the MeCP2 protein (Kyle, Vashi, & Justice, 2018). The most common mutations identified in individuals with RTT are missense mutations with an expected single nucleotide variant count of 229.3 vs. the observed count of 281. The mutations causing Rett syndrome result in a substantial loss or impairment of MeCP2 protein function, disrupting its role in brain development and maintenance (Kyle, Vashi, & Justice, 2018).

To understand the baseline variation in the MECP2 gene, large genomic databases like the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) are examined. Analyzing the non-neuro subset of gnomAD shows a different spectrum of MECP2 mutations than RTT patients. While missense, synonymous, and intronic variants are observed, the frequency of highly disruptive nonsense and frameshift mutations is much lower in this population. Variants found here generally occur at very low allele frequencies. The overall pattern suggests that MECP2 variants common in the general, non-neuro population are less likely to be severely damaging. There is a higher relative prevalence of synonymous variants. Missense variants are predicted to be benign or likely benign. However, this doesn’t mean pathogenic variants are absent; some, like p.Arg115His, are found at very low frequencies, possibly indicating incomplete penetrance or variable expressivity. Allele frequency aids pathogenicity assessment; the relatively high frequency of p.R344W in South Asians led to its classification as likely benign. While the gnomAD non-neuro population harbors various MECP2 variants, the spectrum is enriched for benign or likely benign changes compared to the pathogenic mutations causing RTT, though rare potentially pathogenic variants exist.

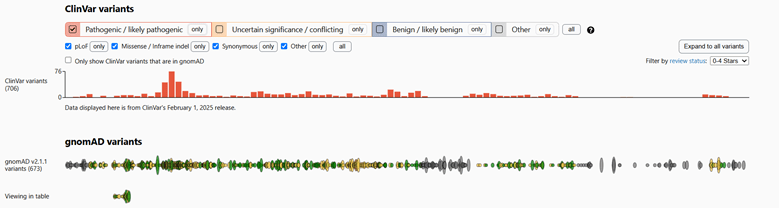

Using the gnomAD 2.1.1 database, I was able to locate four pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations for Rett syndrome. The first pathogenic variation (Variation ID: 143384) is a frameshift mutation, with several submissions on ClinVar alluding to its pathogenicity. The second is a missense mutation (Variation ID: 2505626). The third located mutation is another frameshift mutation (Variation ID: 143360). The final mutation (Variation ID: 11844) had the most highly rated classification of the four, although it is classified as “likely pathogenic” rather than “pathogenic.”

The different mutations within the MECP2 gene lead to diverse outcomes resulting from the relationship between a gene, its protein product’s structure, and function. A protein’s function depends on its shape, which an amino acid sequence determines (Chahrour & Zoghbi, 2007). If there is a mutation in the amino acid sequence, the protein will be disfunctional. The location of a mutation is important, meaning that changes within functional domains are likely to disrupt the protein’s function, which can cause disease (Chahrour & Zoghbi, 2007). Mutations in less important regions may have little impact. Nonsense and frameshift mutations often cause a loss of function and disease. Missense mutations have variable effects depending on the specific amino acid change and location. Synonymous mutations are usually benign but can occasionally affect mRNA processing.

Other factors, like genetic background or, in women, the pattern of X-chromosome inactivation, can influence the outcome (Chahrour & Zoghbi, 2007). A mutation’s likelihood of causing disease depends on how and where it affects the protein. Changes that compromise essential structure or function are classified as pathogenic. Those with less functional impact are classified as benign or likely benign.

| Variation ID | Type of Mutation | Classification |

| 11844 | missense_variant | Likely pathogenic |

| 2505626 | frameshift_variant | Pathogenic |

| 2505626 | missense_variant | Pathogenic |

| 143360 | frameshift_variant | Pathogenic/Likely pathogenic |

Table 1: Variation ID, mutation type, and classification of all pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations for Rett syndrome

Figure 1: gnomAD analysis of MECP2 genetic mutations.

Figure 2: ClinVar and gnomAD variants of MECP2 gene, filtered for pathogenic/likely pathogenic mutations.

References

Chahrour, M., & Zoghbi, H. (2007). The Story of Rett Syndrome: From Clinic to Neurobiology. Neuron, 56(3), 422–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.001.

Kyle, S., Vashi, N., & Justice, M. (2018). Rett syndrome: a neurological disorder with metabolic components. Stephanie M. Kyle, Neeti Vashi and Monica J. Justice, 170216. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsob.170216.

Merritt, J. (2020). On the mechanisms governing Rett syndrome severity. UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/41t7g3m6.

Leave a comment