Nicholas Holmes#, Patrick Muller*, Rishi Patel%, Anisha Tehim&, Atharva Imamdar&, Saachi Yadav&, Sharon Alex&, Vibha Narasayya& and Vinayak Mathur#

# Department of Science, Cabrini University, Radnor, PA 19087

*Eurofins, Chester Springs, PA 19425

%University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104

&Penn Summer Prep Program, Philadelphia, PA 19104

Abstract

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) plays a beneficial role in the evolution and survival of bacteriophages and bacteria. The extent of HGT between Streptococcus bacteria and associated bacteriophages, focusing on viral major capsid proteins, was studied utilizing a bioinformatics approach. Evidence of HGT was identified via the community science analysis pipeline and the BLAST database. Evolutionary relationships were assessed using MEGA software to construct phylogenetic trees. Overall relationships were then represented as networks via the Gephi application. Literature has shown that the major capsid protein in bacteria works analogously to bacterial microcompartments, protecting genetic materials and organelles. These observations, as well as genomic locations of genes coding for major capsid proteins, DNA polymerases, DNA topoisomerases, and other associated molecules, have led to their uses as biomarkers of potential HGT cases. The results provide evidence of extensive HGT between bacteria and bacteriophages, which helps in understanding their evolution and potential therapeutic uses.

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance within bacterial populations is rising to dangerously high levels and new resistance mechanisms are emerging and spreading globally. One such mechanism that has been observed is horizontal gene transfer (HGT). HGT occurs when genetic material is exchanged between organisms in a non-genealogical manner (Goldenfeld and Woese, 2007). This genetic exchange is unlike the genetic exchange which occurs from parent to offspring, as HGT usually occurs between different organisms which are not related. Through the means of HGT, a bacteria can pick up many different functions, including antibiotic resistance and virulence factors. (Deng et al. 2019)

Bacteriophages have shown to have a role in transfer of genetic material between bacteria (Borodovich et al., 2018). Bacteriophages can infect bacteria either through the lytic cycle (called lytic phages) or the lysogenic cycle (called temperate phages) (Rehman et al., 2019). The lysogenic cycle involves the bacteriophage integrating their genome into that of the host cell, and can become dormant, only to infect the cell when it undergoes activation (Labonté et al., 2019). These temperate phages can serve as vectors for HGT between bacterial species via transduction (Labonté et al., 2019). Phage transduction can be studied by examining a bacterial genome and locating the pockets of viral DNA. Phages have effects on the control of bacterial populations, the spread of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance genes, resulting from unique combinations of genetic diversity (Cumby et al., 2015). The mechanism by which these viruses infect bacteria and how these drive their evolution is poorly understood and is crucial to understand where they originated from (Cumby et al., 2015). Bacteriophages have unique host range, and their specificity is determined by their specific structures to attach to specified host bacterial cell receptors and infect the cells.

The protein that we focus on in our study is the major capsid protein. Capsids are the morphological structures that contain the condensed form of the genetic material of a bacteriophage, and also protect it from any outside physical and chemical damages. Recent research has shown that mutations in the genes that code for these proteins are necessary for certain interactions with different host cell receptors and appear to contribute to the stability of a given capsid. This suggests that these mutations aid in broadening bacteriophages’ host ranges (Labrie et al., 2014).

Interestingly, there are similarities between encapsulin proteins that form bacterial structures resembling shells, and the major capsid protein of the HK-97 bacteriophage (Freire et al., 2015). Structural identities are also seen with capsid proteins and S-layer lattice protein components of the cell envelope of prokaryotes and bacteria (Freire et al., 2015). Fusogenic proteins of enveloped viruses which enable the fusion between them and host cell membranes, have also been shown to function analogously to the SNARE family of proteins of Caenorhabditis elegans, which encode for fusion of intracellular vesicles to their cell membranes and allow for cell–to–cell communication (Freire et al., 2015). Not only that, the structures and functions of major capsid proteins and bacterial microcompartments are very similar. Bacterial microcompartments are protein shells that encase enzymes, molecules essential for the microorganism, and may be even their genetic material, protecting these items from degradation or physical or chemical damages in or out of the cell (Krupovic & Koonin, 2017). These notions provide insight into how the ideas and concepts of these proteins encoding capsids that protect their genetic material have expanded from beyond unique to bacteriophages, but to other microorganisms as well.

Bioinformatics analyses and studies have demonstrated bacteria that have undergone HGT with bacteriophages possess conserved genomic regions pertaining to not just to single genes, but multiple, different genes that are located relatively close to one another. According to research presented by Sabath et al., 2012, overlapping genes and sequences are very common in viral genomes. Expressions of these genes have been confirmed, while functionality requires further investigation. Interestingly, the resulting, translated proteins lack a stable, tertiary, three-dimensional structure characteristic of most normal, wild-type proteins (Sabath et al., 2012). In addition to genes encoding major capsid proteins, genes that encode for DNA polymerases, DNA topoisomerases, and other molecules associated with genome replication are inherited through HGT as well. These genes have been shown to be located close together within viral genomes. Appropriately, these genes are termed genomic islands, which refer to groups of unique open reading frames that contain sequences that encode given traits or carry out specific functions (Villa & Viñas, 2019). Examples of genomic islands that have been investigated carry out functions pertaining to virulence and pathogenicity, symbiosis, metabolism, fitness, and antibiotic resistance (Finke et al., 2017). The specific mechanism of HGT involved in how these genomic islands are integrated into the genomes of host organisms remains unknown (Villa & Viñas, 2019). This property provides an opportunity to utilize major capsid proteins as biomarkers when analyzing genomic sequences to establish evidence of HGT amongst bacteriophages and bacteria (Born et al., 2019).

In this study we focused on the major capsid protein in Streptococcus genus of bacteria. Studying how bacteria acquires its resistance to antibiotics is necessary, due to the shrinking list of effective antibiotics. The objective of this study is to assess the extent of HGT between bacteria species and associated bacteriophages, using the major capsid proteins as biomarkers. Our results indicate that overlapping open reading frames composed of varying numbers of base pairs are located close to the major capsid protein in the bacterial genomes. Whether or not these regions encode functional proteins is not entirely known. Current annotations present in databases indicate that these genomic regions encode several different proteins that contribute to the structure and morphology of the major capsid protein (Rosenwald et al., 2014).

Methods

HGT & Community Science Project Pipeline

Positive cases of HGT between bacteriophages and bacteria were determined using the Community Science Project Pipeline (Mathur et al., 2019). A list of accession numbers of bacteriophage major capsid proteins was generated from the NCBI database. Each phage accession number was searched against the bacteria database on NCBI using BLASTp to generate positive hits (referred to as Forward BLAST) (Johnson et al., 2008). The top 10 hits based on the cut-off criteria of e-values of 1e-50 or lower, and a query coverage of 70% or higher, were recorded. The top bacterial hit accession number was then searched against the Virus database on NCBI using BLASTp (referred to as Reverse BLAST) (Johnson et al., 2008). Again, the top 10 hits which satisfied the cut-off parameters were recorded. If the top virus hit accession number in the Reverse BLAST matched the original virus accession number query, that bacteria-virus pair was recorded as a potential positive case of HGT. In total, 75 phage accession numbers were tested to give 21 positive HGT bacteria-virus pairs (Table 1).

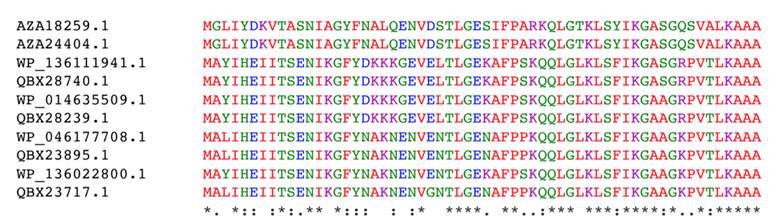

Evolutionary History of Bacteria and Bacteriophages – Comparative Genomics

The evolutionary history of bacteria and bacteriophages was assessed via comparative genomics. FASTA sequences of the major capsid protein from all positive cases of HGT were uploaded to MUSCLE software and aligned (Edgar, 2004). (Supplementary Figure 1). These sequences were then uploaded to the MEGA7 software to generate phylogenetic trees (Kumar et al., 2015). The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on maximum likelihood method and bootstrapping value of 100, seen in Figure 1. Based on the results, the Streptococcus clade of bacteria was selected for further analyses.

Synteny & Evolutionary Relationships

The Streptococcus clade of bacteria and bacteriophages were selected for the synteny analysis. Synteny for the Streptococcus clade of bacteria and bacteriophages was determined using the software MAUVE (Darling et al., 2010). Major capsid gene sequences were downloaded from NCBI for both bacteria and bacteriophages. The Mauve synteny output was generated for all the phages, bacteria and the visualization of the bacteria and phage sequence.

Gephi Network Analysis

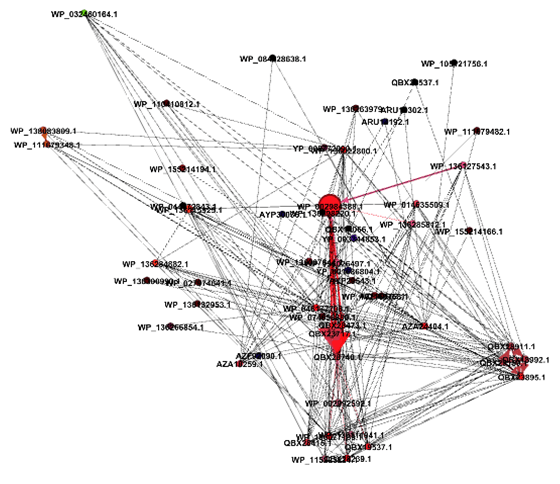

The top six results from the Forward and Reverse BLAST searches were collected based on the Community Science Pipeline and were each organized as a node into the Gephi software for network analysis (Bastian et al., 2009). Connections between bacteria and bacteriophages based on the generated phylogenetic trees were input into Gephi as edges. A node in the center of the network with the most edges connected to it was indicative of the ancestral sequence that was shared by most bacteria and bacteriophages through HGT.

Results

Comparative Genomics

Based on the arrangement on the phylogenetic tree and validation by the bootstrapping values, there is a high likelihood that Streptococcus bacteriophages and bacteria were involved in HGT with respect to the major capsid protein. Despite the major capsid protein being present in the five bacteriophages and bacteria, their location in the genomes of each species varies. This suggests mutations such as translocations and insertions have occurred over time (Kyrillos, et al., 2016). This could explain the divergence of pairs of bacteriophages and bacteria in the phylogenetic tree. One pair that is the most divergent and in its own unique clade and not associated with the other pairs is the connection between the Streptococcus phage VS-2018a and the major capsid protein E in Streptococcus thermophilus.This is also reflected in their MUSCLE alignments that vary compared to the other bacteria and bacteriophage pairs.

Synteny & Evolutionary Relationships

The Mauve software was used to create a multiple sequence alignment and predict synteny of Javan Streptococcus bacteriophage and bacteria pairs using the progressive Mauve algorithm. In the synteny map of the four Javan prefixed bacteriophages, the major capsid protein lies in the range of approximately 500-2000 base pairs. (Supplementary Figure 3). There is a consistent alignment based on the peak height and coloration patterns with Phage VS2018 having the most unique genome arrangement. The S.thermophilus is missing a 400 base pair region upstream of the major capsid protein gene, as indicated by a shift in the sequence alignment (Supplementary Figure 4). The five phage sequences of interest are in reverse orientation in the genome indicated by the peaks falling below the main sequence line in Figure 2. The area between 850-970 base pairs is a unique region found only in S.thermophilus bacteria and the phage VS 2018a pair. This is expected as this pair lies on a separate clade in the phylogenetic tree generated previously. The alignment of the genomes indicates that the region upstream and downstream of the major capsid gene is also shared between these bacteria and bacteriophage pairs. This pattern indicates that there is not just the major capsid gene that is shared between bacteria and phages but instead a whole chunk of the genome.

Gephi Network Analysis

The central node in the network corresponds to a hypothetical protein in Streptoccoccus pyogenes. As seen in the top six results of the Reverse BLAST, this node has multiple shared edges with a major capsid protein in Streptococcus bacteriophages Javan 146, 454, 464, 474, 459, 484, 166 (Figure 3). The generated network shows that the connections are the same as they appear in the phylogenetic tree. The central node of the gene encoding a hypothetical protein in S.pyogenes connects closely to different strains of itself and a Javan bacteriophage 464. This relationship suggests that those two bacteria and bacteriophage pairs could be where the initial transfer of genomic material had occurred.

Discussion

HGT of the major capsid protein has allowed for Streptococcus bacteriophages and bacteria to display survival of the fittest to survive in constantly changing environments. In doing so, greater genetic diversity is achieved through HGT, thus potentially speeding up adaptation and overall evolution.

Upon review of the scientific literature, the role and functions of major capsid proteins

could potentially serve as a bacterial microcompartment protecting the bacterial genome from

physical and chemical damages akin to the functions of viral capsids, as a result of HGT (Krupovic & Koonin, 2017). Interestingly, there are similarities in morphology

between the S-layer lattice proteins present in mostly archaea bacteria. Based on this notion,

perhaps these proteins function as a means to protect the genetic material of archaea from

physical or chemical damages. Perhaps even archaea evolved to possess such as a structure from

HGT as a means to survive in its native environment of hot springs or areas of high temperature

(Freire et al., 2015).

It has been suggested that bacterial genes acquired through HGT are usually quickly deleted from the genome unless they are to be utilized for some specific reasons later on (Rosenwald et al., 2014). For example, genes acquired through HGT that improve metabolism in bacteria can be expressed under given circumstances. It is upon changes in the environment or medium that render these genes functionless that can result in the deletion of the genes. This is understandable as bacterial genomes tend to be very compact and constituent (Moran, 2002). This most likely occurs as a means to conserve internal energy by not expressing genes that are not necessary or will not be considered as such. These notions can be both determined via RNA sequencing techniques in which the protein of interest is isolated, its messenger RNA is extracted and purified from other RNA molecules, for study (Rosenwald et al., 2014).

By identifying HGT within the major capsid protein sequences for the Streptococcus bacteria and the bacteriophages that infect them, we can begin to understand the extent of HGT within bacterial populations. We propose that the major capsid protein can be used as a biomarker to identify HGT in other bacteria species as well. There is evidence to suggest that when genes are transferred horizontally, it is not just a single gene but a whole genomic region consisting of multiple genes (Szöllősi et al., 2015). A future direction of this research would be to identify the gene regions flanking the major capsid protein in the bacterial genome and understand the functionality of those genes and the role they play within the bacteria.

In this study, we focused on the Streptococcus genus, but it can easily be expanded to include a larger dataset of bacteria and bacteriophage pairs based on data availability in the NCBI database. It is imperative to study the extent and rate of HGT in bacterial populations as it is a key mechanism for bacteria to acquire antibiotic resistance genes, and thus has implications for human health worldwide.

References

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009). Gephi: an open-source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Print. N. P. Retrieved from https://gephi.org/users/publications/

Born, Y., Knecht, L. E., Eigenmann, M., Bolliger, M., Klumpp, J., & Fieseler, L. (2019). A major-capsid-protein-based multiplex PCR assay for rapid identification of selected virulent bacteriophage types. Archives of Virology, 164(3), 819–830. doi: 10.1007/s00705-019-04148-6.

Borodovich, T., Shkoporov, A. N., Ross, R. P., & Hill, C. (2018). Phage-mediated horizontal gene transfer and its implications for the human gut microbiome. Research in Microbiology, 169(7-8), 366-373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmic.2018.04.005

Cumby, N., Reimer, K., Mengin‐Lecreulx, D., Davidson, A. R., & Maxwell, K. L. (2015). The phage tail tape measure protein, an inner membrane protein and a periplasmic chaperone play connected roles in the genome injection process of E. coli phage HK97. Molecular Microbiology, 96(3), 437-447. doi:10.1111/mmi.12918.

Darling, A. E., Mau, B., Perna, N. T. (2010). progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS ONE, 5(6), 1-17. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011147

Deng, Y., Xu, H., Su, Y., Liu, S., Xu, L., Guo, Z., Wu, J., Cheng, C., & Feng, J. (2019). Horizontal gene transfer contributes to virulence and antibiotic resistance of Vibrio harveyi 345 based on complete genome sequence analysis. BMC Genomics, 20(1), 761. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-019-6137-8

Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research, 32(5), 1792–1797. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh340

Finke, J. F., Winget, D. M., Chan, A. M., Suttle, C. A. (2017). Variation in the genetic repertoire of viruses infecting Micromonas pusilla reflects horizontal gene transfer and links to their environmental distribution. Viruses, 9, 116. 1-18. doi: 10.3390/v9050116.

Freire, J. M., Santos, N. C., Veiga, A. S., Da Poian, A. T., & Castanho, M. A. R. B. (2015). Rethinking the capsid proteins of enveloped viruses: multifunctionality from genome packaging to genome transfection. The FEBS Journal, 282(2015), 2267–2278. doi:10.1111/febs.13274

Goldenfeld, N., & Woese, C. (2007). Biology’s next revolution. Nature, 445(7126), 369. https://doi.org/10.1038/445369a

Johnson, M., Zaretskaya, I., Raytselis, Y., Merezhuk, Y., McGinnis, S., & Madden, T. L. (2008). NCBI blast: a better web interface. Nucleic Acids Research, 36, 1-5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn201.

Karp, P. D., Billington, R., Caspi, R., Fulcher, C. A., Latendresse, M., Kothari, A., … Subhraveti, P. (2017). The BioCyc collection of microbial genomes and metabolic pathways. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 20(4), 1085–1093. doi:10.1093/bib/bbx085

Krupovic, M., & Koonin, E. V. (2017). Cellular origin of the viral capsid-like bacterial microcompartments. Biology Direct, 12(25), 1-6. doi:10.1186/s13062-017-0197-y

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., & Tamura, K. (2015). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0. Print. N. P. Retrieved from https://www.megasoftware.net/web_help_7/hc_citing_mega_in_publications.htm

Kyrillos, A., Arora, G., Murray, B., & Rosenwald, A. G. (2016). The presence of phage orthologous genes in Helicobacter pylori correlates with the presence of the virulence factors CagA and VacA. Helicobacter, 21(3). doi: 10.1111/hel.12282

Labonté, J. M., Pachiadaki, M., Fergusson, E., McNichol, J., Grosche, A., Gulmann, L. K., … Stepanauskas, R. (2019). Single cell genomics-based analysis of gene content and expression of prophages in a diffuse-flow deep-sea hydrothermal system. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, 1-12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01262.

Labrie, S. J., Dupuis, M., Tremblay, D. M., Plante, P., Corbeil, J., & Moineau, S. (2014). A new microviridae phage isolated from a failed biotechnological process driven by Escherichia coli. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 80(22), 6992-7000. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01365-14.

Lerner, A., Matthias, T., & Aminov, R. (2017). Potential effects of horizontal gene exchange in the human gut. Frontiers in Immunology, 8, 1-14. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01630.

Mathur, V., Arora, G. S., McWilliams, M., Russell, J., & Rosenwald, A. G. (2019). The genome solver project: faculty training and student performance gains in bioinformatics. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 20(1), 1-12. doi:10.1128/jmbe.v20i1.1607

Moran, N. A. (2002). Microbial minimalism: genome reductionin bacterial pathogens. Cell, 108(5), 583-586. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00665-7

Rehman, S., Ali, Z., Khan, M., Bostan, N., & Naseem, S. (2019). The dawn of phage therapy. Reviews in Medical Virology, 1-16. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2041.

Rosenwald, A.G., Murray, B., Toth, T., Madupu, R., Kyrillos, A. & Arora, G. (2014). Evidence for horizontal gene transfer between chlamydophila pneumoniae and chlamydia phage. Bacteriophage, 4(4). doi: 10.4161/21597073.2014.965076.

Sabath, N., Wagner, A. & Karlin, A. (2012). Evolution of viral proteins originated de novo by overprinting. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 29(12). doi:10.1093/molbev/mss179.

Szöllősi, G. J., Davín, A. A., Tannier, E., Daubin, V., & Boussau, B. (2015). Genome-scale phylogenetic analysis finds extensive gene transfer among fungi. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 370. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0328

Villa, T. G. & Viñas, M. (2019). Horizontal gene transfer: breaking borders between living kingdoms. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

Yang, Z., Zhang, Y., Wafula, E. K., Honaas, L. A., Ralph, P. E., Jones, S., … dePamphilis, C. W. (2016). Horizontal gene transfer is more frequent with increased heterotrophy and contributes to parasite adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(45), 7010-7019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608765113.

Table 1: Table of the positive cases of HGT amongst pairs of bacteriophages and bacteria.

| Bacteriophage | Bacteriophage Accession Number | Bacteria | Bacteria Accession Number | |

| putative head protein [Riemerella phage RAP44] | YP_007003622.1 | hypothetical protein [Riemerella anatipestifer] | WP_014938289.1 | |

| putative head protein [Brevibacillus phage Osiris] | YP_009215022.1 | hypothetical protein [Brevibacillus laterosporus] | WP_022583694.1) | |

| major capsid protein [Streptococcus phage Javan464] | QBX28740.1 | major capsid protein E [Streptococcus pyogenes] | WP_136111941.1 | |

| major capsid protein [Arthrobacter phage Isolde] (not top hit) | AYR00888.1 | hypothetical protein [Arthrobacter sp. cf158] | WP_091323596.1 | |

| phage major capsid protein [Cellulophaga phage phi18:1] | YP_008240963.1 | phage major capsid protein [Elizabethkingia anophelis] | WP_059330774.1 | |

| phage major head protein [Oenococcus phage phiS13] | YP_009005240.1 | hypothetical protein [Oenococcus oeni] | WP_032811398.1 | |

| major capsid protein [Streptococcus phage Javan446] | QBX28239.1 | hypothetical protein [Streptococcus pyogenes] | WP_014635509.1 | |

| major capsid protein [Streptococcus phage Javan146] (not top hit) | QBX23717.1 | major capsid protein E [Streptococcus pyogenes] | WP_136022800.1 | |

| major capsid protein [Brevibacillus phage Jimmer1] | YP_009226318.1 | phage capsid protein [Brevibacillus laterosporus] | WP_119733365.1 | |

| major capsid protein [Streptococcus phage Javan166] | QBX23895.1 | hypothetical protein [Streptococcus dysgalactiae] | WP_046177708.1 | |

| hypothetical protein [uncultured Mediterranean phage uvMED] | BAQ84158.1 | hypothetical protein [Elizabethkingia anophelis] | WP_151449511.1 | |

| major capsid protein [Streptococcus phage VS-2018a] | AZA24404.1 | major capsid protein E [Streptococcus thermophilus] | AZA18259.1 | |

| major capsid protein [Streptococcus phage Dp-1] | YP_004306931.1 | hypothetical protein D8H99_54145 [Streptococcus sp.] | RKV76237.1 | |

| major capsid protein [Mycobacterium phage Renaud18] (not top hit) | AXQ64918.1 | MULTISPECIES: major capsid protein E [Mycobacteroides] | WP_057970215.1 | |

| prophage major head protein [Oenococcus phage phiS11] | YP_009006573.1 | hypothetical protein [Oenococcus oeni] | WP_032811892.1 | |

| hypothetical protein [Oenococcus phage phi9805] | YP_009005184.1 | hypothetical protein [Oenococcus oeni] | WP_032820248.1 | |

| capsid protein [Mycobacterium phage TChen] (not top hit) | AWH14408.1 | MULTISPECIES: major capsid protein E [Mycobacteroides] | WP_057970215.1 | |

| capsid protein [Arthrobacter phage KellEzio] | YP_009301281.1 | hypothetical protein DRJ50_09715 [Actinobacteria bacterium] | RLE21106.1 | |

| major capsid protein [Microviridae sp.] | AXH73898.1 | hypothetical protein [Elizabethkingia anophelis] | WP_080670996.1 | |

| major capsid protein [Streptococcus phage Javan464] | QBX28740.1 | major capsid protein E [Streptococcus pyogenes] | WP_136111941.1 | |

| major capsid protein [Microviridae sp.] | AXH77365.1 | |||

Figure 1: Phylogenetic tree of all of the positive cases of HGT. There are multiple, unique clades observed. The center Streptococcus clade was chosen for further analysis based on the high bootstrap values.

Figure 2: The synteny of the phage and bacteria sequences of interest generated via Mauve. The five phage sequences are in reverse orientation in the genome indicated by the peaks falling below the line. The area between 850-970 base pairs is a unique region that is only found in S.thermophilus bacteria and phage VS 2018a pair. This is expected as this pair lies on a separate clade in the phylogenetic tree generated from MEGA7.

Figure 3: The Gephi network of all positive HGT cases within the Streptococcus clade. Notice that all bacteria and bacteriophages display evolutionary relationships through a mechanism of HGT.

Supplementary Figure 1: MUSCLE alignment of the Streptoccoccus bacteria and associated bacteriophage pairs. The accession numbers, AZA24404.1, QBX28740.1, QBX28239.1, QBX23895.1, and QBX23717.1 are bacteriophage major capsid proteins. The rest of the sequences are bacterial proteins. All of the sequences are highly conserved here.

Supplementary Figure 2: Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree using MEGA7 showing the relationships amongst Streptococcus bacteriophages and bacteria.

Supplementary Figure 3: The synteny of the four Javan prefixed phages generated via Mauve. The solid red line connecting each sequence shows the location of the matching section of the genome. The major capsid protein lies in the range of approximately 500-2000 base pairs in this alignment. There is a mostly consistent alignment based on the peak height and coloration patterns. Phage VS2018 has certain regions which are unique as can be seen by the sliding black box feature.

Supplementary Figure 4: The synteny of S.thermophilus and S.dysgalactiae generated via Mauve. S.thermophilus is missing a 400 base pair region upstream of the major capsid protein gene, indicating by the shift in sequence alignment.

Leave a comment